I started this article by researching AI tools for UI creation like v0, Bolt, Lovable, and the recent Figma Make. But, as I was organizing my ideas, I realized that to talk about these tools in the context of the design process, I needed to clarify what I meant by design process. And so, unintentionally, I ended up with a giant text that I eventually divided into two parts. The first describes the design process and its challenges at each stage, with some ideas on how AI can influence it. The second focuses on UI generation tools. I hope you enjoy reading it as much as I enjoyed writing it!

The design process involves ideation and validation when creating a product. This can take many forms: it can be a rigid process with differentiated ideation and construction stages (iterative or not) or a process that mixes these stages with continuous experimentation and validation. It can also be collaborative, merging team roles or the user/designer distinction. These variations are also conditioned by the business context (whether the product is B2C, B2B, or subject to regulations).

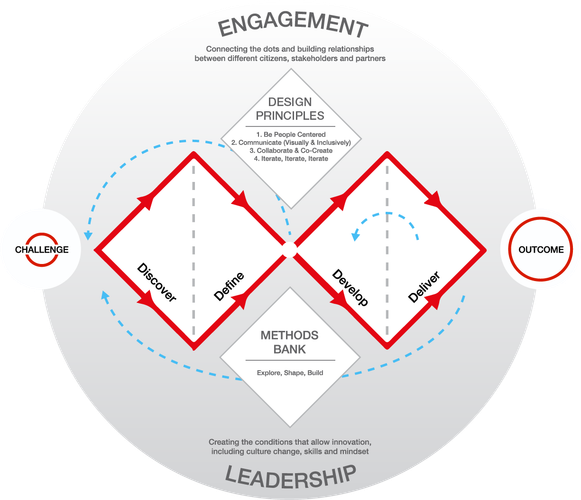

In other words, there are many variables. That’s why it’s common to simplify and describe the concept with the Double Diamond framework created by the British Design Council in 2005. The Double Diamond process is straightforward: start with a challenge, explore ideas (discovery), then refine and define them. Next, gather feedback to explore implementation options (develop), and finally simplify and converge to deliver the product. Though called “double,” the process could be seen as a single diamond as both parts are similar.

Let’s examine the stages of the design process more closely to understand how we can take advantage of AI tools.

The British Design Council’s Framework for Innovation, an expanded version of the Double Diamond framework.

The IDEO Shopping Cart, a project showcased in 1999 on ABC Nightline news show, became iconic as a prime example of Design Thinking. It’s amusing to read the comments on numerous YouTube copies of the video, frequently shown in innovation classes. The most interesting aspect of this video is not the shopping cart itself but the detailed insights into the design process. If you haven’t watched it, I highly recommend it. You have probably never seen this particular shopping cart anywhere. Lesson: The design that survives is not always the most convenient to the user, but it is the one that also balances business needs.

The Story of the Ribbon, a 2008 presentation by Jensen Harris, the manager of the Office UX team at the time, recounts the design process behind the Office redesign.

Challenge

Just as every story has a “call to adventure” that motivates action, the design process begins with a “challenge.” In Design Thinking, this is called “empathizing,” because the challenge arises from understanding what people need. And even if you do it for money, you still have to connect with users; otherwise, who will buy from you? (Unless they have no other choice, of course).

In design, the hardest part isn’t creating the perfect solution but understanding the problem well. The more complicated the problem, the harder it is to identify. This means that discovering and defining the problem are processes that go hand in hand and mutually affect each other.

Discovery

The discovery phase is one of the most entertaining for designers, and one of the most terrifying for engineering managers, because it can last as long as one wants or give the feeling of going in circles.

During the discovery phase, AI tools not only help take notes and summarize things from the Internet, but also we can use them to create interfaces and improve our understanding. For example, we ask someone to tell us their “ideal solution,” and we instantly create an interface to show them and receive their opinion. It’s an additional tool for generative research activities.

However, they have some limitations. First, needs are not always verbalized, making their translation into prompts difficult. Second, generated UIs can seem “ready” and make us think that everything is solved, when in reality, we need to continue exploring. Third, we can get stuck with what we see on the screen and lose the complete vision of the problem (although, to be fair, that’s not AI’s fault).

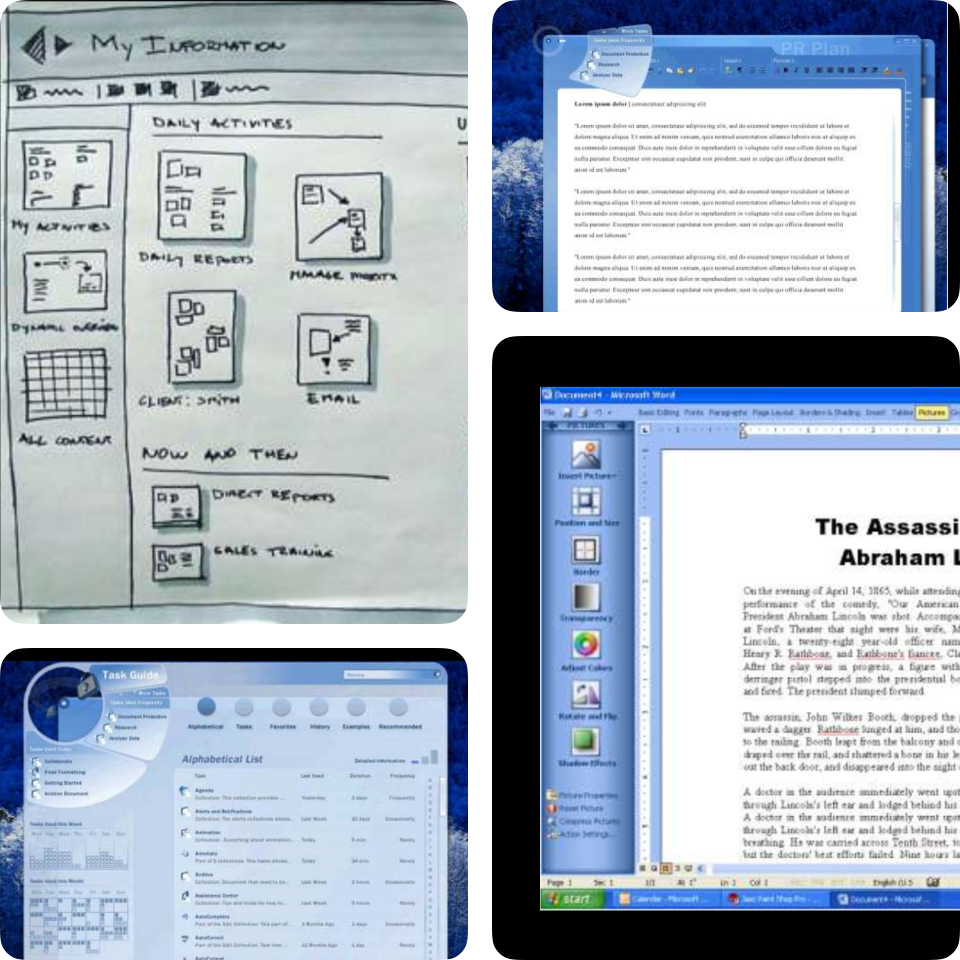

These are some examples taken from the The Story of the Ribbon presentation. The Office team explored many UI options as part of the Office re-design.

Definition (Convergence)

After discovery, in the Definition stage, we gather everything to clearly understand the central problem we will solve. We move from asking, “What’s happening here?” to focusing on, “What is the specific problem?”

With generative UI tools, one might be tempted to skip this stage. Why waste time with so much analysis if I can start prototyping the solution immediately? But this is a trap. Without a proper focus, prototyping ends up with more back-and-forth.

Development and Delivery

How a product is developed and delivered depends heavily on the product type and business.

There are two main approaches: prolonged internal iteration (like Apple with the iPhone) and rapid launch and external iteration (with the famous MVP popularized by Lean Startup). Both strategies have their place in business.

In the design process, both approaches follow the same pattern. In the first case, the “development” phase can be interpreted as the creation of prototypes, and “delivery” as validation with users. The second is the development and launch of a functional product version.

The key to both is learning. Without learning to iterate on the product, the essence of this “double diamond” process is lost.

In 2025, AI tools that generate UI cannot generate 100% functional products, although some “vibe coding” enthusiasts say otherwise. However, they are good enough to create prototypes and proofs of concept.

And that’s all, for now.

This first part was a tour through the design process, or at least a generic description.

AI tools open new possibilities for obtaining feedback and iterating on ideas. But beware, although one can accelerate stages using AI, skipping them without understanding user needs will not magically result in a good product, no matter how good the “vibe coding” tools are.